To stream, or not to stream?

Streaming music through services like Spotify doesn't make sense for some musicians, but what are the facts and figures?

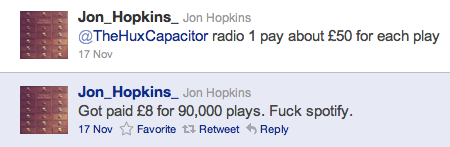

Mercury-nominated Jon Hopkins has caused quite a stir with his exasperated tweet, “Got paid £8 for 90,000 plays. Fuck Spotify.” His outburst came just as anit-Spotify sentiment was reaching a head, and has effectively polarized the music community. With acts like Coldplay, Adele, and Tom Waits refusing to put their new releases on the platform, and with indie distributor ST Holdings' recent decision to pull their catalogue from all streaming services, it seems the Spotify-refuseniks have the upper hand. But are they right to be so disparaging? Does Spotify really “cannibalise the revenues of more traditional digital services”, as ST Holdings claim?

When Spotify first launched it was universally applauded and embraced by the musical community. Online streaming wasn't new, even then, but here, finally, was a service with the momentum and critical mass to genuinely change the listening habits of a nation. Only die-hard music geeks are interested in “possessing” music, went the argument; this was a platform aimed at those who would otherwise download or stream their music illegally. And that has been the rallying cry for all Spotify defenders of late: “the cheques might be small, but it's still better than nothing!”

Lady Gaga: 1m streams = £100?

Stories recounting tales of woefully small royalty pay-outs get an awful lot of coverage in the media. The furore surrounding Hopkins' outburst is much the same as the shock-wave that spread through the industry when it was claimed that Lady Gaga only received £100.76 for a million plays of Poker Face in 2008. That claim has since been proved to be false (in fact, Spotify paid out £201.53), and the streaming service claims the low payout was because at the time the platform was still in its infancy, but confusion still abounds. The fact remains that the only way to know how much Spotify pays out is to actually receive a cheque from them. The band Little Things That Kill released their sales data recently, and that showed in June 2011 they earnt about 0.4 Eurocents per stream; a figure that they suggest is on the rise. And this rise tallies with my own experience. In April 2010 I got roughly 0.04p for each stream, compared with 0.2p this June. If I got Hopkins' listening figures then I'd earn £180 for his ninety thousand plays, but then I am self-released so I get all the label-cut as well.

Like for Like: Spotify vs. Radio Royalties

At the current rate, it takes nearly three hundred Spotify plays to earn what I get from just one download on iTunes, and Jon Hopkins compared his £8 for 90,000 streams to the £50 he'd get from just one play on Radio 1. These figures are all accurate, but do they actually tell us anything? These kinds of comparisons aren't really comparing like for like, and as such they're of little use. If you take into account the number of listeners to Radio 1 and count each of those as a single stream, then the figures look a whole lot more favourable. According to RAJAR, Radio 1 reached just shy of 12 million people in the quarter ending September. Assuming only a tenth of those listeners heard a particular broadcast of Hopkins' track, then according to his £50 figure he'd be making the equivalent of 0.004p per 'stream' and would only have made £3.75 from Spotify if they used the same rate. There are a lot of assumptions in that calculation and Radio 1 pay more than most radio stations, but even so it's safe to say that Spotify is much the same as terrestrial UK radio play, and we shouldn't get too upset about it.

Where the argument gets a little more tricky is when you consider that people might be using Spotify not as a radio service, but as a replacement for actually buying records. This is the argument made by Coldplay et al, and it's one that looks less kindly on Spotify's model. How many times do people listen to albums on average? Someone would have to listen to a ten-track album end to end 500 times to equal the £10 one would pay for an album direct from the band at a gig (again, lots of assumptions here, and the wholesale price of albums to retail outlets is markedly less than £10). Not an unreasonable task for my Desert Island Disks, perhaps, but the majority of albums in my collection have only been listened to a handful of times at least, and many have never been listened to end to end.

Breakage

In the physical world, these records – bought but never played – fall under the category of 'breakage', and constitute a not-inconsiderable proportion of the income for old-fashioned labels. What the try-before-you-buy nature of the current market is doing is effectively eliminating this kind of breakage from the system. The move toward streaming as the primary method for consuming music is rightly scary for those who stand to lose a substantial portion of their income, but it's nevertheless the way the market is heading.

And isn't a world where music is paid for on a per-play basis a more equitable one? Eventually streaming subscription rates and music producers expectations will level out, a compromise will be reached, and bands will get paid for being popular. We may never see the like of super-star multi-million-pound advances again, but the success of what musical stars we do have will be founded on the willingness of people to actually listen to their music. I'm sure the few remaining major labels will find a way to circumvent this naïve and idealistic meritocracy, but it's still a nice dream to have.